This article was co-authored with Dr. Manoj Kumar Das and originally published in the March issue of the Research Journal Communication Today. Click on the cover of the Journal to access the article there.

Introduction

In an era when convergent technologies have enabled user-generated content to provide a substantial portion of information consumed worldwide, media education has assumed a new dimension. Indeed, the European Union Ministers of Education at the Istanbul conference, feeling the pulse of the future, as early as October 1989, had set the agenda for media education thus: “Pupils should develop the independent capacity to apply critical judgement to media content. One means to this end and an objective in its own right should be to encourage creative expression [in] the construction of pupils’ own media messages, so that they are equipped to take advantage of opportunities for the expression of particular interests in the context of participation at [the] local level (as cited in Masterman, 1997, p. 15).”

This agenda has two dimensions to it. First, the audience must learn to differentiate between propaganda and news on the one hand, and advertisement and public service announcement on the other (Buckingham, 2013). At the same time, they should be enabled to use media effectively and ethically since they are today both producers and consumers of content (Masterman, 1997; Bruns, 2016). Thus, media education no longer becomes only a specialized professional course but also an exercise in media literacy targeted at the general populace (Bruns, 2016). Second, with almost everyone now possessing the ability to generate content, it becomes imperative that media professionals, teachers, and researchers be offered more specialized training in all fields concerning the media industry so that distinction between media enthusiasts and media professionals is maintained (Masterman, 1997; Bruns, 2016).

During the 1990s and particularly with the liberalization of the Indian economy and the subsequent expansion of the mass media industry in the nation, media education took a serious turn as more and more universities began to set up mass communication departments to offer undergraduate and postgraduate courses as well as research programmes. Media literacy, meanwhile, remains a neglected area in Indian academia, at least in the sense that had been envisioned by the UNESCO Declaration on Media Education of 1982[1] and the World Summit on Media Education 2000. Mass communication has been made part of class ten syllabi only by few school boards such as the Council for Indian School Certificate Examination (CISCE) and National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS) through which the younger generation has been introduced to media literacy. At the state level, fewer state

[1]UNESCO uses the term ‘media and information literacy’ instead of media education primarily to give impetus to media literacy which remains a neglected area. For more on this, see Kumar, 2007.

secondary and higher secondary school boards have introduced media literacy in their respective syllabus. These include only West Bengal, Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. In states like Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra, media literacy is imparted outside school hours primarily through the efforts of NGOs, social action groups, and women’s groups (Kumar, 2007). Given that Sikkim does not have a separate school board of its own, and the majority of its schools are affiliated under CBSE that does not offer media literacy as an optional course, children in the state of Sikkim have remained hitherto unexposed to media literacy.

Media education in Sikkim has followed the larger national pattern. Given her history, however, there are many peculiarities associated with media development and media education in the state. It must be noted here that Sikkim became part of the Indian Union in 1975 and the transition from monarchy to democracy has had its natural implication on media and media education in the state. It is thus important that any discussion on media or media education in the state in contemporary times has to be, in the backdrop of its history. In this paper, we therefore briefly engage in an examination of the growth of media in the state in the light of its historical context even as we underscore the background and training of human resource involved in various media sectors in the state. Formal education in the field of media started in the state with the establishment of Sikkim University in 2010, and we discuss this in the paper. We then highlight some key milestones at the level of formal media education in the state that was initiated by Sikkim University in 2010. We conclude by dwelling on the status of media education in the state before we submit our overall conclusion.

Mass media and media education in Sikkim: The context

Sikkim became a part of the Indian union on the 16th of May 1975 after a referendum was held to depose the King and merge with India (Phadnis, 1980). She thus became the last Indian protectorate to merge with India and was directly incorporated as the 22nd state of the Indian union due to her peculiar circumstances and her strategic location (Phadnis, 1980). After the merger with India, Sikkim effectively transformed from a feudalistic monarchy to a modern democracy (Phadnis, 1980).

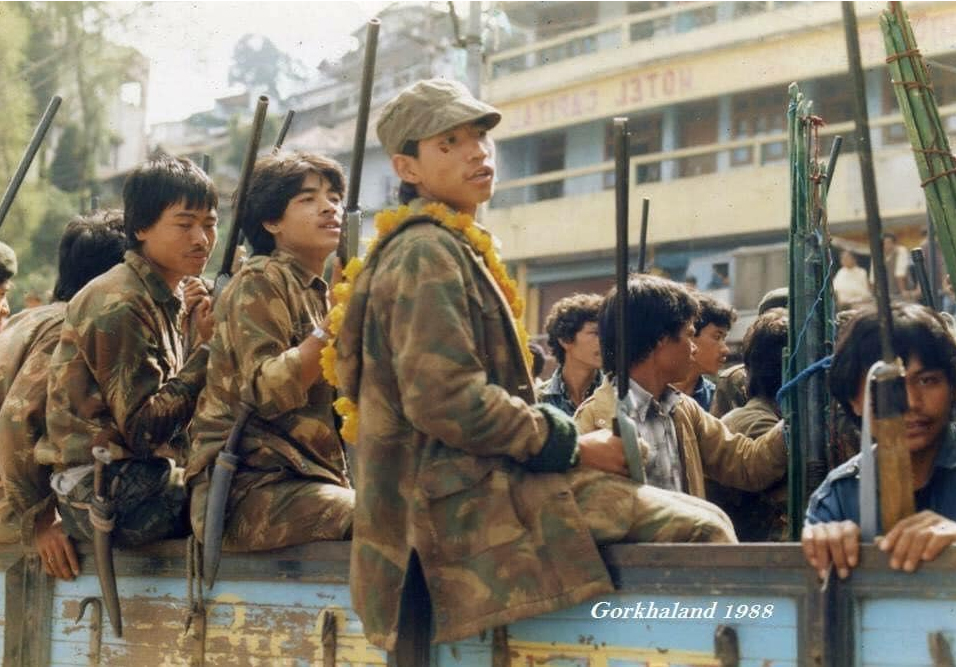

Ruled by a feudal-theocratic clique, Sikkim was an isolated and backward region. Education, health care, agriculture, transportation, commerce, and industry were highly neglected (Datta, 1998; Lama, 2001). Education was monastic. As Datta (1998) writes, “Education in pre-merger Sikkim was rather conservative, helping the upper class in perpetuating the feudal privileges and domination in the society. The educational opportunity was not universalized while it was restricted to the feudal upper-class people” (p. 2). Under these circumstances, mass media grew as an instrument of popular democratic mobilization against the Sikkimese monarchy and the feudal-theocratic clique (Datta-Ray, 1984; Duff, 2016). The present-day districts of Darjeeling and Kalimpong in the state of West Bengal played an important role in its development given Sikkim’s geographical, social and cultural proximity to the region (Roy, 2012). The pioneering journalists in the state were educated in Darjeeling or major cities in India and they looked upon journalism more as a calling than a profession (Roy, 2003). It is no wonder that a majority of journalists were teachers, lawyers, politicians or activists. In the absence of formal media education, they learned the ropes of the trade through practical experience and sheer fortitude (Deepak, 2014).

Sikkim’s merger with India and her transformation from monarchy to democracy led to a major change in the field of journalism in the region. It brought an end to activist journalism and ushered in an era of professional journalism. Professional journalists took over from school teachers, lawyers and politicians (Deepak, 2005). Journalism also transformed into professional media enterprises effectively modelled according to profit-making principles. Experience in journalism became a key feature along with an enterprising disposition. In 1976, Ram Patro began the publication of Sikkim Express an English newspaper merely a year after the merger with India. It was followed by Himali Bela which began to be published as a newsweekly on the 13th of November, 1977. Himali Bela became a daily newspaper on the 15th of August, 1978. It was the first Nepali daily newspaper to be published in India. They were followed by Himgiri, Samachar Darshan, Sikkim Observer, The Voice of Sikkim, Naya Pariparti, Teesta Rangit, Frontier Samachar, Bisfot, Wichar among many others. The state, no longer isolated and closed to the outside world now, started attracting educated and talented youths from other states in the field of journalism and other sectors including but not limited to academia, bureaucracy, and the hospitality industry.

Television made its debut in Sikkim in 1982 when Doordarshan Kendra Gangtok was started. The station initially started as a relaying station, broadcasting programmes from DD National, New Delhi. The employees of Doordarshan were and continue to be trained through various programmes and workshops organised in-house throughout the nation (Khashu, 2001).

As in the rest of the nation, cable television came to the state in the 1990s. Nayuma Cable was a pioneering initiative on this front. Originally known as Sikkim Cable Television, Nayuma Cable besides offering access to a plethora of television channels also maintained camera crews as well as a studio and broadcast important proceedings like Governor’s address, question hour, address of the chief minister at the Legislative Assembly and other important events. Crews received hands-on training or were sent to nearby Siliguri or Kolkata in West Bengal for training (Shresta, 2005). In October 2016, ABN TV was launched. It became the first Nepali language satellite television channel to cater to the 2.9 million Nepali speaking Indians scattered across the nation. The channel based in Siliguri, however, was shut down by West Bengal Police[1] and could not make a comeback (Sharma, 2017). ABN TV attracted a large number of prominent journalists from the region and had become a good place for honing skills as frequent in-house workshops and training programmes were organised by the organisation. Most of the media professionals of the channel were trained in prominent institutes of the nation such as Film and Television Institute, Pune and Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute, Kolkata.

Radio was introduced in the state in 1960 when the All India Radio (AIR) Gangtok station was established by the Government of India to counter Chinese propaganda (Datta-Ray, 1984). The station was manned largely by Indian professionals and was initially a relay station. Few programmes in Nepali were broadcast and Radio Jockeys and technicians were trained at AIR Kurseong in Darjeeling district (Roy, 2003). AIR Gangtok began broadcasting on its own in the 1980s. It also organises training workshops for its employees as well as enthusiasts as part of a broader AIR training programme. In the recent decade, commercial FM radio has also become a major player in the mass media industry in the state. Radio Misty 95 FM was launched in Gangtok on the 31st of January, 2009. It was quickly followed by Red 93.5 FM Gangtok which made its debut on the 6th of March, 2010. Most of the Radio Jockeys and technicians have been trained in different states or were working in other major FM radios before they joined these FM stations. In recent years numerous online news portals have also mushroomed which has added a new dimension to mass media. Operated mostly by young enthusiasts these portals have become an alternative to traditional news media. Some of them also possess degrees in mass communication.

Formal media education in Sikkim

There were no government universities in Sikkim until the establishment of the Sikkim University, a Central University established by an Act of Parliament in 2008. All colleges in the state, including the government colleges, till then, were affiliated with North Bengal University based in nearby Siliguri in West Bengal. The Department of Mass Communication in North Bengal University was established in 2000, and the first college to impart undergraduate course in mass communication in the region was Siliguri Degree College. Sikkim did not lag behind and introduced mass communication as an undergraduate course in Government Degree College in Namchi. With the establishment of Sikkim University, all the colleges in the state, including Namchi Government college, became its affiliate institutes. Incidentally, Namchi Government College is the sole college in the state providing the undergraduate programme in the subject to date.

The priority attached to mass communication as a subject by Sikkim University is reflected in the launch of its postgraduate programme in subject two years after its establishment. Even before the teaching department was set up in June 2010, a six-member expert body was constituted to form the Curriculum Development Committee (CDC). The responsibility to develop a syllabus for the MA programme in the subject was entrusted to the CDC. The committee members included: Prof. Biswajit Das, Director, Centre for Culture, Media and Governance, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, Prof. T.K. Thomas, Director, Vivekananda Institute of Professional Studies, New Delhi, Prof. Gita Bamezai, Indian Institute of Mass Communication, New Delhi, Ms Lalita Panicker, Senior Associate Editor, Hindustan Times, and Mr Roshan Kant Ghisingh, Director, Arena Animation, Darjeeling. In its workshop held on February 26 and 27 the same year, the CDC under the Chairmanship of Prof. Biswajit Das finalised the MA syllabus. The CDC underscored the need to make the programme an interdisciplinary one and stressed the need for pedagogic and knowledge creation and simultaneously train the students for the industry. Accordingly, a well-conceived modular structured syllabus was designed giving adequate attention to both theory and practice.

The Department of Mass Communication started functioning after the appointment of four faculty members through an all India interview process. The founding members of the faculty were: Mr Manoj Kumar Das, Dr Anamika Roy, Mr Ilam Parithi and Ms Krithika Subramania – all Assistant Professors. The first author of this paper was appointed as the Co-ordinator of the Department as per University norms. The Department started operating from its temporary campus at Saramsa in the outskirts of Gangtok town. In 2012, a fresh appointment process was initiated to recruit regular teaching faculty for the Department. The Department currently has a team of four regular faculty members and takes the help of two to three guest faculty members every semester.

During the first years of the launch of its MA programme, the Department attracted students from as far as Lakshadweep, Kerala, Haryana. Students from Bihar, West Bengal, Assam add to the multi-linguistic character of the Department and reflect a national character of the University. Local students from Sikkim constitute a reasonable share of the student community. Emerging areas in the subject such as media policy, media and politics, media, movement and rights, among others, were included in the course and students from other departments in the University showed keen interest in these credit-based courses. The research programme in the Department started in 2012 with the start of the integrated M.Phil-Ph.D course. In 2014, the Department started taking direct admission to its M. Phil and PhD programme. With its vibrant research programmes, it will not be wrong to say that the Department spearheaded a serious academic initiative in the field of media education in the region. A key thrust of the research programmes in the Department has been to better understand different aspects of the media sector in the region – an area that has hitherto been ignored. Students and teachers in the department have significant publications to their credit, and these include a book by Routledge (currently in production stage). Papers by students have been selected in prestigious international conferences. Students for both MA and research programmes in the Department are chosen through an admission test conducted across major towns and cities in the country.

The Department maintains a well-equipped recording studio, editing suite, and a multi-media lab. Over the past decade, the it has been able to install equipment worth around a crore of rupees. Equipped with state of the art audio-visual production technologies, the Department trains students in print media, radio, and audio-visual production. The editing suite has iMAC and Mac Pro systems with Final Cut Pro X and Adobe After Effects editing software. Multi-cam consoles with a 24-channel audio mixing monitor add to it. High-end video cameras like Canon EOS 7D Mark II, Sony PMW 150, and still cameras with a variety of lenses enrich the laboratory. Audio editing software like LogicPro and Pro Tools, among others, enable the students to have hands-on training in the field of radio/audio production. The Department is also equipped with a full outdoor audio recording facility, and regularly updates its equipment to move along with the times.

Over the past decade, the Department of Mass Communication of Sikkim University has seen around 150 students successfully earning their postgraduate degree. While some of them have taken up a career in the field of professional journalism in the state as well as outside, some have secured jobs in the Information and Public Relations department (IPR) of the state government. Few of the students have also taken to teaching in various universities and colleges in and outside the state contributing thereby to media education in the country. And still, others have launched their own media/production houses. It may not be wrong to say, therefore, that the University has ushered in a new phase of media education in the region and is benefiting the overall ecosystem of media training in the country.

Conclusion

Media literacy in Sikkim, in comparison with other states like Kerala, Karnataka, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu, whose respective school boards offer mass communication as a part of the syllabus, is found wanting. The role played by NGOs in imparting media literacy is also a much-neglected field. NGOs have played a prominent role in media literacy in the country. Organisations like Media Foundation based in New Delhi have been sponsoring research projects, studies, publications, lectures, seminars and discussions as well as promoting training courses (Kumar, 2007). It has also published well-acclaimed books in the field of mass media. However, such organisations are very few in India. SIGNIS India, for instance, is one such non-profit organisation that has been engaged in training in mass communication. It conducts media courses outside school hours and is one of the reasons behind the southern states of Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu faring well in this direction. SIGNIS India or similar organisations, however, do not operate in Sikkim.

Media education as a specialized course of study in the state is still an emerging field in the state. The establishment of colleges and universities in the state itself has been a recent phenomenon. It was not until 2010 that media education began in right earnest in the state with the establishment of the postgraduate department of mass communication at Sikkim University. The state – before her merger with India and before her transformation from a monarchy to a democracy – neither had a well-developed educational system nor a well-established mass media industry. It was only after the merger in 1975 that earnest efforts on both fronts were made. It is safe to say that media education is at an embryonic stage in the state given its very brief history and the peculiar conditions that the state has had to endure in not so distant past. The growth of the media sector in the state in recent times and the concomitant demand for trained media professionals in the area, however, point towards ample scope and need for media training and education in the state.

References

Bhutia, T. O. (2019, December). Prof. Sisir Basu coaches Mass Comm students on research methodology. Voxpop, p. 6.

Bruns, A. (2016). User-Generated Content. In J. D. Klaus Bruhn Jensen, The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy, 4 Volume Set (pp. 2108-2112). New York: Wiley.

Buckingham, D. (2013). Media Education: Literacy, Learning and Contemporary Culture. New York: Wiley.

Datta, A. (1998). Sikkim since independence. New Delhi: Mittal Publications.

Datta-Ray, S. K. (1984). Smash and Grab: Annexation of Sikkim. New Delhi: Vikas.

Deepak, S. (2005). Role and Contribution of Kanchenjunga in the Development of Press in Sikkim. Namchi: Nirman Prakashan.

Dewan, D. B. (2012). Education in Sikkim: An Historical Retrospect – Pre-merger and Post-merger Period. Tender Buds’ Society.

Dewan, D. B. (1991). Education in the Darjeeling Hills: An Historical Survey, 1835-1985. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company.

Duff, A. (2016). Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom. Penguin.

Khashu, P. K. (2001). A critical study of training in tv production and technical operations for Doordarshan staff conducted at FTII and consequent designing and planning a revised training programme. Pune: Savitribai Phule Pune University.

Kumar, K. J. (2007). Media Education, Regulation and Public Policy in India. UNESCO Paris Conferenceon Media Education. Paris: UNESCO.

Lama, D. M. (1997). Makers of Indian Literature – Thakur Chandan Singh. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi.

Lama, D. M. (2001). Sikkim Human Development Report. Gangtok: Government of Sikkim Social Science Press.

Masterman, L. (1997). A Rationale for Media Education. In R. W. Kubey, Media Literacy in the

Information Age: Current Perspectives (pp. 15-65). Transaction Publishers.

Ministry of Human Resource Development. (2020). National Education Policy 2020. New Delhi: Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India.

Paget, W. H. (1907). Frontier and Overseas Expedition in India. London: Intelligence Branch, Army Headquarters.

Phadnis, U. (1980). Ethnic Dimensions of Sikkimese Politics: The 1979 Elections. Asian Survey, 1236-1252.

Poddar, P. (2008). Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures – Continental Europe and its Empires. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Pradhan, I. (1997). Parasmani Pradhan. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi.

Pradhan, I. (1997). Parasmani Pradhan. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi.

Prashar Bharati. (2013). Industrial Training Report. New Delhi: Prashar Bharati.

Rawat, M. K. (2019, December). Do not tweak idealism in Journalism: Nagraj. Voxpop, p. 3.

Risley, H. H. (1973). The Gazetteer of Sikhim. New Delhi: Oriental Publishers.

Robinson, A. (1989). Satyajit Ray: the inner eye. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Roy, B. (2003). Fallen Cicada – Unwritten History of Darjeeling Hills. Darjeeling: Sanjay Biswas.

Roy, B. (2012). Gorkhas and Gorkhaland. Darjeeling: Parbati Roy Research Foundation

Scott, A. M. (2008). Controlling the New Media: Hybrid Responses to New Forms of Power. Modern Law Review, 491-516.

Sethia, K. (2016, November 26). Road to Sikkim. International Film Festival of India.

Sharma, A. (2017, August 23). For a month now, India’s only Nepali satellite news channel has been facing an unofficial ban. Scroll.in.

Shresta, R. S. (2005). Sikkim, Three Decades Towards Democracy: Evolution of the Legislative System. Gangtok: Sikkim Legislative Assembly Secretariat.

Skoda, U. (2014). Navigating Social Exclusion and Inclusion in Contemporary India and Beyond: Structures, Agents, Practices. Anthem South Asian Studies, 137.

Subba, J. R. (2008). History, Culture and Customs of Sikkim. New Delhi: Gyan Publishing.

Subba, T. B. (1992). Ethnicity, State, and Development: A Case Study of the Gorkhaland Movement in Darjeeling. New Delhi: Har Anand Publications.

[1]The main office through which programmes were broadcast was based in Siliguri and was shut down by the police as a part of a clamp down due to the Gorkhaland agitation in the districts of Darjeeling and Kalimpong (Sharma, 2017).